Ned Kelly — bushranger, murderer, or folk hero?

Ned Kelly is a landmark in Australian history. One of the last bushrangers from the late 1800s, Edward (Ned) Kelly, never had a chance.

His famous last words were, “Ah, well, I suppose it has come to this.” Interpreted by journalists, these words have been passed down as “Such is life.”

It’s a great saying, and I’ve used it many times when I’ve been down and when something has gone wrong.

Doomed from the start

Ned was born in Beveridge, a small town north of Melbourne in the heart of gold mining country. Ned’s parents, John and Ellen, were of Irish descent. John was a convict deported from Ireland for stealing pigs.

They were a poor family of eight children. Ned was the eldest, who assumed responsibility for the family after his father’s death in 1866. At the age of sixteen, Ned served three years of hard labor as part of his sentence for horse stealing.

The Kelly’s had a long history of cattle and horse rustling for extra money to support the family.

Ned was a ticking time bomb. He hated how corrupt cops mistreated poor people, especially the Irish. It was one such officer who sparked the demise of Ned Kelly.

The start of the Kelly gang

Police Constable Fitzpatrick went to the Kelly farm. He was there to arrest Ned’s 17-year-old brother for stealing a horse. While there, he attacked Ned’s sister, Kate. The outraged Kellys were not known to back down from a fight, and in the struggle, Fitzpatrick was shot in the wrist.

Although the shooter was never confirmed, he blamed Ned (whom he had it in for right from the start). Ellen, Ned’s mother, was convicted of attempted murder. She received a three-year prison sentence.

Enraged by the injustice and with a warrant for his arrest, Ned fled into the bush with his brother, Dan. They were later joined by two friends, Steve Hart and Joe Byrne. The Kelly gang had been formed.

Later that year, four officers camped at Stringy Creek. They were Kennedy, Lonigan, McIntyre, and Scanlon. They were searching the bush for the Kelly gang. The Kelly gang found Scanlon and McIntyre when the other two were away hunting. They confronted them. Scanlon refused to surrender, and in the ensuing scuffle, he was shot by Ned.

Lonigan and Kennedy returned and confronted the gang. In the gunfight, both were killed. McIntyre escaped and alerted the local police.

Now declared outlaws, the four Kelly gang members could be shot on sight. They lived in the bush for two years. Supporters helped them. They believed they were fighting for the poor against a corrupt police force.

The Final Showdown

Ned tried to explain his actions in a letter known as the Jerilderie Letter, in the year before his showdown. He was the only bushranger known to take such action. The letter ended with the chilling statement:

“I am a widow’s son, outlawed, and my orders must be obeyed.”

Tired of running and feeling victimized, he and his gang chose to act against the police. They planned an attack on the Glenrowan police station.

On June 26, 1880, they shot Aaron Sherritt, a former friend. Ned thought he had become a police informant. The gang rounded up Glenrowan residents. They held them hostage at the local hotel. At the same time, they made others destroy the railway line. They knew that reinforcements were being sent by train from Melbourne.

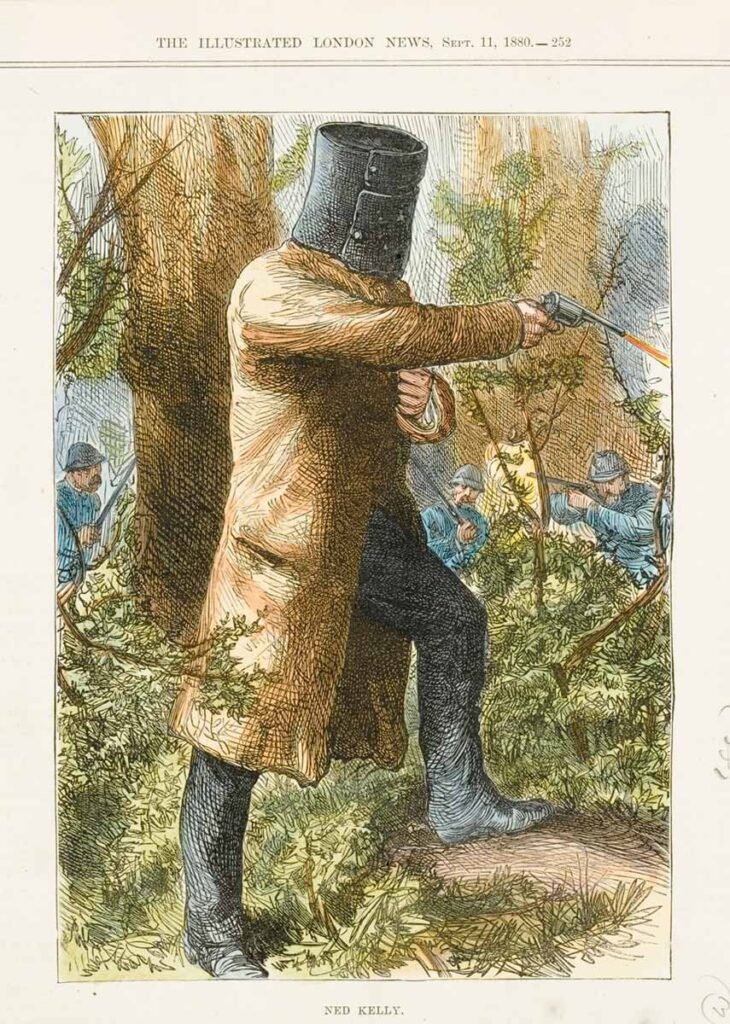

One of the hostages escaped and managed to warn the train driver of the danger. In the early hours of the morning, officers from the train surrounded the Glenrowan hotel. The gang put on their homemade armor, specially made for the encounter, and prepared to fight.

As the gang stepped out of the inn, the large group of police opened fire. Stray bullets injured many of the captives inside the building. Eventually, the gang released the women and children hostages.

Ned retreated into the bush behind the hotel with the idea of circling behind them. At daybreak, an eerie-looking figure emerged from the bush. Ned’s armour had a significant flaw: it didn’t protect his legs.

After a brief gunfight, police shot Ned in the legs and captured him. Joe was also shot. Dan and Steve, still in the hotel, released the last hostages before the police set fire to the hotel. It is believed they took their own lives to avoid capture.

Such is life

Although Kelly had only the most basic education, he is known for his sayings. During his last talk with the judge, he said, “No one understands my case like I do.” His final words were, “I will see you there, where I go.”

He was hanged at the Old Melbourne Gaol on November 11, 1880. This occurred despite 32,000 people signing petitions for a pardon.

His last meal was his favourite: roast lamb and peas, accompanied by a bottle of claret. Rumors say he secretly married his long-time love, Ettie Hart. She is Steve Hart’s sister, and the wedding took place just before his execution.

To some, Ned Kelly was a hero, standing up for Victoria’s poorest and fighting the corrupt police. He died a man of honor to his friends and was fiercely loyal to his family.

He is hailed by some as the first stand against oppression and as a call for an Australian republic.

Today, you might see him as a scoundrel, a murderer, or a hero fighting oppression. Either way, his impact on Australian culture is clear.

There are sayings such as “to be as brave as Ned Kelly” that romanticize his stand.

Here’s a final point: A study of people with a Ned Kelly tattoo showed that 74% died from unnatural causes. Of those, 40% were suicides and 11% were homicides. The study revealed that individuals with a Ned Kelly tattoo could be at a higher risk of unnatural death.

Spooky!

The ethical dilemma Kelly represented is interesting. He was hounded by a corrupt police force. Despite killing two policemen (which some argue was in self defense) he gave a lot of his stolen money back to he suppressed poor at the time.

Till next time,

Calvin